Embodied Cosmogony: Purusha Meeting Christ

“From that sacrifice in which everything was offered, the verses and chants were born, the metres were born from it, and from it the formulae were born.”

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being.”

When learning about the Vedic creation stories, I cannot help but draw connections to the Christian tradition. I am, admittedly, a perennialist when it comes to comparative studies of religion; therefore, it is understandable that I am making connections between these two religions given this hermeneutical context. First, however, one must begin reading texts through the objective and postmodern lens. It is crucial for perennialists to not only emphasize the connections and syncretic ideas between the philosophies or theologies, but also to fully understand the context of the studied topic. In other words, one cannot make connections without a deeply rooted knowledge of the studied religions, philosophies, or theologies. A careful study of the many Hindu philosophical texts in the classroom setting allows for this deepening of knowledge and provides the foundation to develop my own perennialist interests and find connections between the Vedic and Judeo-Christian creation accounts. Vedic hymnology and Christian mythology regarding the creation of existence are similar in regards to both using the image or figure of a human (man) to describe the formation of the universe. Before examining these anthropomorphic deities, one should first understand where they--or all of creation--came from: the nothingness.

The RgVedic hymn Nasadiya begins by claiming that “there was neither non-existence nor existence” and that even “darkness was hidden by darkness in the beginning; with no distinguishing sign, all this was water” before the formation of the universe. Stating that neither non-existence (asat) nor existence (sat) ‘existed’ before creation came into being echos, but does not directly correspond to, the formless void of the creation account in Genesis: “the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep.” The main difference between these two texts is understanding what the traditions believe existed within this non-existent/void thing before creation. Genesis claims that God (Creator) was in the beginning and thus created everything from/within this formless void, whereas the RgVedas leave room for questioning whether or not God (non-existent intelligence) even knows how creation arose.

“Whence is this creation? The gods came afterwards, with the creation of the universe. Who then knows whence it has arisen? Whence this creation has arisen--perhaps it formed itself, or perhaps it did not--the one who looks down on it, in the highest heaven, only he knows--or perhaps he does not know.”

Understanding that there is open ambiguity in the Vedas and devout certainty in the the Judeo-Christian accounts provides a foundation upon which one may further ask ‘how?’. Indeed this question regarding how the material universe came into existence has been asked for thousands of years. Philosophies, theologies, and now the sciences have all had their hand in trying to make sense of this question. Can something come from nothing (ex nihilo)? Can nothing create something? Both the RgVedas and the gospels in the Christian tradition call upon an anthropomorphic image which is sacrificed for the purpose of creating the universe.

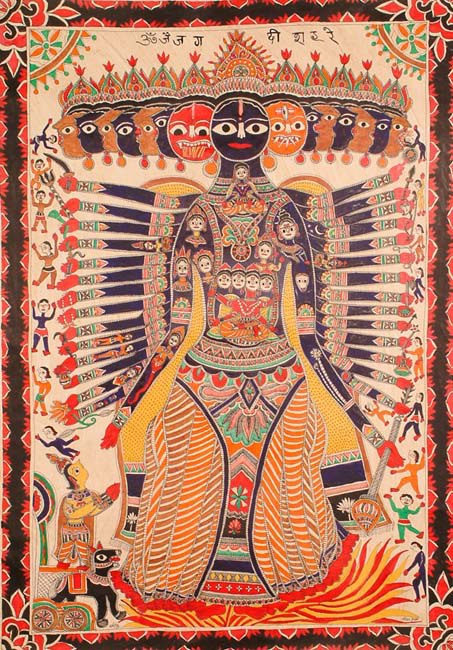

In the RgVedas, more specifically in the Purusha-Sukta, the Cosmic person is described as the body of the universe that has been sacrificed in order for creation to come into existence. “The well-orchestrated primeval sacrifice of the Cosmic Person by the gods results in the formation of the various constituents of the celestial, natural and social orders.” This understanding of creation should come as no surprise due to the historical and cultural context of the Brahmanic emphasis on ritualistic sacrifice. “With the sacrifice the gods sacrificed to the sacrifice. These were the first ritual laws.”

The use of language regarding sacrifice is not abnormal for Christian incarnational theology. Indeed, the Christ-like figure represented in the human/material form is Jesus, whose body is sacrificed for a greater good--i.e. the sins of the world/creation. Though the initial purpose of sacrificing Jesus is different from the sacrifice of the Cosmic Person, one cannot ignore the possible connections between the role of the ‘Word’ in the Gospel of John and the sacrifice Purusha. Meister Eckhart, a thirteenth/fourteenth century Dominican philosopher, offers commentary on the creation account at the beginning of the gospel of John, that can be used to point out the similarities between the gospel and the RgVedic ‘Hymn of Man’.

Eckhart begins by using imagery of a seed to describe how Jesus--the Word--was with God in the beginning of creation, and revealing Christ’s relation to God. “What proceeds is in its source; it is in it as a seed is in its principle, as a word is in one who speaks; and it is in it as the idea in which and according to which whatever proceeds is produced by the source.” What should be emphasized here is the concept that whatever is produced by the source (i.e. the tree/Christ/Son/material body/existence) contains in it the idea of the original source (the seed/God/Father/spiritual body/non-existence). Drawing upon this statement, one can deduce that because Jesus Christ--Jesus being the human/material aspect and Christ representing the divinity--was with God in the beginning, not above God nor below God, but with God; the ultimate sacrifice was an embodied sacrifice of Jesus. In other words, the representation of Jesus as Christ being sacrificed on the cross for the purpose of humanity/creation can be compared to the sacrifice of Purusha who is both a divine God and the embodiment needed for the creation of the universe.

Again, I am a perennialist so my studying of these texts is already preconditioned to find connections at the risk of potentially not being objective enough. Yet, the similarities between the Purusha and Christ are profound seeing as both rely on the non-existent divinity (i.e. God-self, Brahma, Father), the anthropomorphic embodiment of this non-existence (i.e. Cosmic Human, Atman, Son), and the sacrifice of the latter for a greater purpose (for creation).